Summary – Bank of New York Mellon v. Preciado

The Bank of New York Mellon v. Preciado, 224 Cal. App. 4th Supp. 1 (Cal. Super. Ct. 2013) – Court Invalidates Service Because of Insufficient Proof of Service of Notice to Tenant

This case was decided in August, 2013, and the Supreme Court ordered it to be published in March, 2014.

A published opinion from the Appellate Division of the Santa Clara County Superior Court has invalidated a trial court judgment against tenants in a foreclosure matter because, inter alia, the plaintiff failed to establish that service of the notice was proper, based upon the proof of service. The case consolidated two unlawful detainer actions. One was filed against the owner of a foreclosed property, and another against the tenants in one of the units in the building.

Plaintiff, The Bank of New York Mellon (Bank) retained a registered process server who served notice on both the owner and tenants by posting the notice and mailing copies. Because there was no mail service at the subject property, a mailing was also perfected at a P.O. Box. The server provided proof of service which stated that “after a due and diligent effort”, the notice was posted and mailed to the tenants.

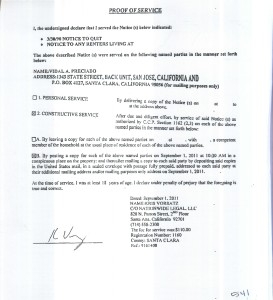

Proof of Service relied on by the court in Bank NY Mellon v. Preciado (Click to enlarge in new window)

The foreclosed owner (FO) defendant responded to the complaint, as did the tenants who filed a pre-judgment claim. Both claimed that service was “littered with gross procedural irregularities”. The FO defendant stated he saw no posted notice but received a copy at his post office box. The tenants claimed that they received no notice on their door or in the mail.

The court wrote that “[a]s a prerequisite to filing an unlawful detainer action, a tenant must be served with either a three, 30, or 90 days’ notice, depending on the individual’s status as a tenant.”

The manner of service employed here, the statute required that “if a place of residence and usual place of business cannot be ascertained or a person of suitable age or discretion cannot be found there, then [service is made] by affixing a copy in a conspicuous place on the property and delivering a copy to a person residing there, if such a person can be found, and also sending a copy through the mail addressed to the tenant at the place where the property is situated (post and mail service). A notice is valid and enforceable only if the lessor has strictly complied with these statutorily mandated requirements for service. (Losornio v. Motta (1998) 67 Cal.App.4th 110, 113–14 [78 Cal. Rptr. 2d 799]; Liebovich v. Shahrokhkhany (1997) 56 Cal.App.4th 511, 513 [65 Cal. Rptr. 2d 457].)” (emphasis added)

Most process serving statutes in California are to be liberally construed, meaning any minor defects in service are generally allowed if the defendant is not prejudiced by the defect. Because the Unlawful Detainer Act sets forth specific statutory requirements, service must be made in strict compliance with the statute. Deviations from the specific statutory requirements are not allowed, but can be remedied with other evidence of compliance.

At trial, Bank asserted that when a registered process server provides proof of service, California Evidence Code § 647 eliminated the necessity for the server to be called as a witness, because “[t]he return of a process server … upon process or notice establishes a presumption, affecting the burden of producing evidence, of the facts stated in the return.” (quoting Palm Property Investments, LLC v. Yadegar, 194 Cal.App.4th at p. 1427.)

Because the Bank did not proffer the server as a witness, the court had to rely solely on the server’s proof of service to determine whether whether the Bank gave proper notice under CCP § 1162. The server’s proof of service of the notice merely stated that “[a]fter a due and diligent effort”, service was made by posting and mailing.

The court relied on two prior decisions in their determination as to whether the Bank had complied with the statute.

In Highland Plastics, Inc. v. Enders (1980) 109 Cal.App.3d Supp. 1 [167 Cal. Rptr. 353], the appellate court analyzed whether there was sufficient evidence that the landlord complied with the “post and mail” provision of section 1162. They recognized that although due diligence is not required for service of the notice, it does mandate that posting and mailing is only allow “[…] if the tenant cannot be located for personal service that the person making this substituted service first determine[s] either that the tenant’s ‘… place of residence and business cannot be ascertained, or that a person of suitable age or discretion there cannot be found.” The deputy marshal testified that he had attempted service, and found nobody there, and posted the notice and mailed it. The appellate court concluded that there was substantial evidence supporting the trial court’s finding that there had been a proper service of the notice.

In Hozz v. Lewis (1989) 215 Cal.App.3d 314 [263 Cal. Rptr. 577], the appellate court held that the trial court properly found that the landlord’s “post and mail” service of a three-day notice was adequate. The landlord’s agent testified at trial that he went to the apartment, rang the bell and knocked on the door, and when no one answered, he taped a copy of the notice to the door and slipped another copy under the door. He then mailed another copy addressed to the tenant.

In this case, the court said that a “post and mail” service is not authorized as a first-resort method of service. Here, [the server’s] declaration does not […] establish that Bank complied with section 1162 as it does not show that personal service was ever attempted. The proofs of service do not state that Appellants [FO and tenants] were not home or that no one of a suitable age was home when the server posted the notice “in a conspicuous place.”

Unlike in Highland Plastics, Inc. and Hozz, the servers in those cases testified as to the circumstances that led up to the posting and mailing. The necessary elements of service were described in court to establish that the landlord plaintiffs strictly complied with the service statute, curing any apparent defect in service. Here, the court could only rely on the four corners of the server’s proof of service. Lacking all of the elements required in the statute, the Bank could not establish that they strictly complied with the statute.

Although this reported decision is not binding on all courts, it will expand tenant defendants with persuasive authority to attack the proof of service without the server’s testimony to support it. Therefore, a proof of service should track the language of the statute so that all of the elements of service are present.

Linked here is a fillable exemplar proof of service to a tenant meeting all the elements of service.

See full Opinion here

Back to California Process Serving Cases and Opinions

Back to Process Server Institute